Essaïda-Carthage: Between the Past and the Future

“The fact is that the people of statues are mortal. One day, our faces of stones will break up in their turn. A civilization leaves behind its mutilated traces, like the pebbles of Hop-o’-My-Thumb, but history has eaten everything up. An object is dead when the living eye cast upon it has disappeared […]”.1

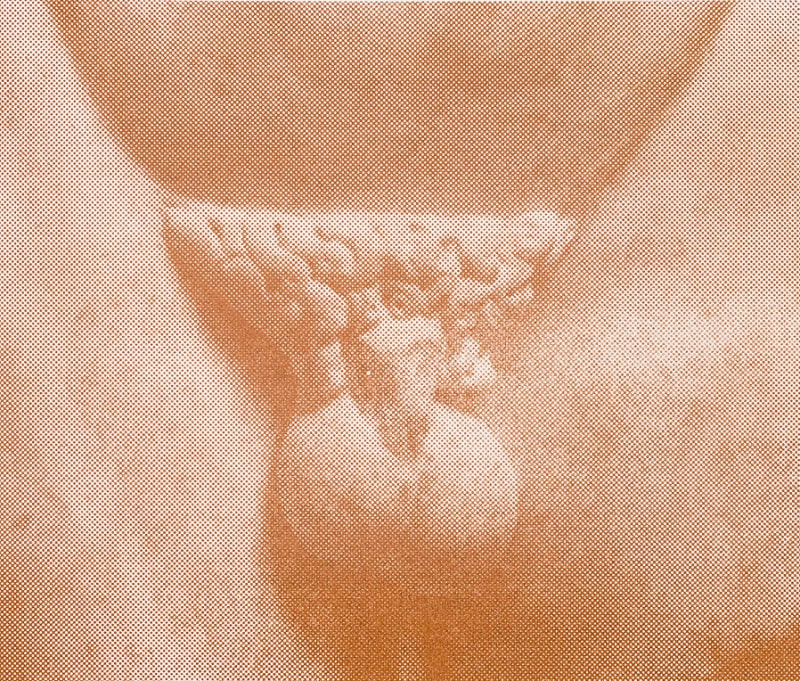

It is as a ceramicist that Malek Gnaoui has become acquainted with earth, its modelling as clay, and its firing, which in turn has led him to appreciate its endless complexity and symbolic meaning. Earth, sand, oxides, pigments, minerals, water and fire are just elements which come from subsoils, just like man, from which he is taken and to which he is destined to return. This feeling is often expressed in the many links that exist between the human factor and the earth, which has incidentally inspired almost all manner of belief and culture in their original myths. Like an archaeology of the past whereby he contemplates the present, Gnaoui is preparing an archaeology of the future on the basis of which our successors will question us. As a committed artist keenly aware of contemporary societal issues, a native of Gabes, in Tunisia, has diversified his activities by developing other forms of visuality, such as social visuality, bypassing traditional forms which manipulate the earth, in order to question the potential of the material and its symbolism, therefore, lending his work a political angle. The history of art and contemporary art sometimes manages to create connections and links between fragments of civilization and life which do not only produce new outlooks, but often succeed in shedding light on certain realities which go unnoticed. In this respect, Gnaoui is not interested solely in the narratives of the victors, the ones we learn in history lessons, but also in those which pass by word of mouth, from memory to memory, from grandparents to grandchildren. These narratives are not composed only of words, but may at times take on aesthetic and traditional forms, or assume manifestations of the immaterial cultural heritage, and the same applies to style, décors, and stylistic ornamentation that we find in embroidery, ceramic decoration and ornamental models. The exhibition Essaïda-Carthage might be a result of this kind of narrative, or rather of its de-construction, thanks to which it permits these different narratives to collide, complement one another and sometimes to contradict each other. The history of this narrative is already that of Tunisia, a complex land on whose soil so many peoples and cultures have followed one another, that people often say about this country that it has been a crossroads of civilizations. For example, Berbers, Ottomans, Normans, Greeks, Romans and Phoenicians, most of the peoples, cultures and religions of the Mediterranean, and even further afield, have passed across its lands and, despite a widespread practice of Damnatio Memoriae, that erasure of memory that victors inflict upon the vanquished, particularly by destroying monuments and buildings, every culture has left behind it signs, marks, wealth, and a part of its identity, thus forming a country enriched by all these accumulated legacies, which are often lumped together in a syncretic and unwitting way. This complexity is a source of wealth in an age of tensions and forms of radicalization, whether religious, social, or economic. This might be the essential message of this show. Scenography for Essaïda-Carthage is constructed like a salute to that archaeological approach that, layer by layer, leafs through each stratum of solidified silt, as if deposited by time, gathering dust and burying civilizations. The circuit is devised in such a way that the viewer becomes involved in a dialogue with the objects, and, as if at an excavation site, becomes progressively ensconced in time, while objects return to the surface and deliver their secrets. In the chapel there is an imposing composite Venus, a blended and arbitrary construction based in part, according to the artist, on the fate of the Bardo Venus2 discovered in Carthage, on whose body a head had been affixed for a while before the head it currently possesses was reinstated fifteen years later. The circuit is also formed by materials taken directly from the Essaïda district, and in particular from the rubble of building sites, such as iron bars and sheets of corrugated iron, whose trivial nature is heightened by metal suggesting gold. This illusion demonstrates the paradox of coating debris with a luxury not associated with such construction materials, which seems to anticipate the future and potentially the value of heritage that will possibly inform the objects which, in a more or less remote future, will acquire the status of archaeological vestiges. An office allows visitors to interact with forms of testimony and samples, including collections of imprints, kinds of poetic palimpsests which unite the memories of the walls that shelter and distribute the daily round of the inhabitants of Essaïda, inventoried in a form of book, symbol of memory and knowledge. Showing an interest in no-go urban areas is tantamount to confronting the impasses and difficulties of contemporary Tunisian society. The historian Sami Kamoun has recently reminded us3 that the arrival of the French protectorate had very heavy consequences with regard to the urbanization of Tunis. The construction of a new urbanistic model totally altered the social composition of the Medina, and impoverished the local people by removing middle-class families from the houses and palaces, while at the same time absorbing waves of poor emigrants of rural origin. The transformation, to borrow his words, of “a peripheral field of olive trees on the edge of the medina into an illegal suburb” is an irreversible phenomenon, with heavy social consequences for its inhabitants who, on a daily basis, suffer all manner of social and economic ostracism. The reputation of these neighbourhoods, fuelled by phobias and prejudices about poverty, suffers because of violence, drugs and prostitution, and their residents are the first victims of such scourges, as has been shown by the geographer Habib Ayeb in a valuable study of the inhabitants of Saïda Manoubia.4 Being a stranger or foreigner in a place where one is a prisoner… If the inhabitants of Saïda have hailed from a migration from the south, centre and west of Tunisia, as well as from impoverished down-town families, the presentday generation has often been born in this neighbourhood, which means that the population is at once native and rejected, as if an outsider in its own home. This twofold feeling of belonging and exclusion increases the sense of confinement and marginalization. According to the researcher, it is this “virtual and psychological line between the city and the neighbourhood which, by being established as a barrier that cannot be crossed, lends material form to the spatial and social marginality of Saïda and its residents.”5 When Malek Gnaoui started thinking about this exhibition project, he swiftly made the link between the marble Venus in the Bardo Museum and the concrete dolphins which decorate the modest homes of Essaïda. Although separated by periods of time, civilizations, and materials, the marble Venuses and the concrete dolphins are linked by a mythological continuity, which has lent its name to the show. Venus incarnates, herself, the connection between periods and this fabulous territorial and cultural adventure which has produced modern Tunisia. The Roman goddess takes on many forms and names in the civilizations which dominated the earlier periods, and we find her with the identity of Greek Aphrodite, herself the issue of the Syrian-Phoenician goddess Astarte, in turn an avatar of the Assyrian-Babylonian goddess Ishtar. The goddess incarnates survival through the transformation of traditions, which do not necessarily die, but rather adapt and change. Celebrating this wealth and embracing the diversity of its roots is an essential key to self-knowledge and the acceptance of the other, and possibly even a key to liberating Essaïda’s inhabitants. Malek Gnaoui’s exhibition, is dedicated to those inhabitants, attempts to expose these territories by identifying the physical and mental barriers that confine them. By observing, in particular, the architecture and the environment of Essaïda, and establishing temporal connections, he disrupts the linearity of time, and re-examines an often relentless and invariably suffered social determinism. By focusing on architectural ornaments, and putting those archaeological times into perspective, he astonishingly creates cultural bridges and demonstrates how the inhabitants of Essaïda, this “New Carthage”, are also heirs to this cultural diversity and this wealth, as perceived in a way by the character of Amine, the painter, searching for inspiration in the noteworthy film of the same title made by Mohamed Zran.6 What will remain of these territories and how will future anthropologists and historians judge our societies, and based on what evidence? The division of wealthy neighbourhoods and popular neighbourhoods, and inequalities with regard to life expectations, access to healthcare and education? A collective responsibility involving protecting the weakest? And the responsibility of other countries, either neighbouring, or former colonial powers? With the Mediterranean dream administratively and politically prohibited at the gates of European shores, how, in the future, will countries justify their divisions and their borders? How will we manage to put up with injustice? These crucial questions appear implicitly in Malek Gnaoui’s work and some of his projects have already attested to his interest in youth living in Tunisia’s underprivileged neighbourhoods. The fragments of walls in which he has enclosed the sounds of conversations purloined from those youth at a loose end, and which he presented at B7L9 Art Station in Bhar Lazreg, powerfully embodies the spirit that marks the place with an imprint, both positive and negative. Such experiences and memories gathered are central to the exhibition “0904”, presented as part of Dream City 2019 which explored the 09th of April Prison in Tunis, led him, from encounter to encounter and story to story, he formed connections between fragments, and brought awareness to the importance of conservation, the dissemination of memory, and the collective duty that this accumulation represents. Through Essaïda-Carthage, he uses the past as a witness, along with the barely perceptible micro-narratives, and the archaeological traces that he identifies and observes in their current manifestations. The relation of the concrete and ornaments of the houses built illegally, without a permit, that draw from a repertory of traditional forms, also incorporate these new constructions, which have gradually become permanent within cultural history. In his practice, we have acknowledged how Malek Gnaoui recorded memory in order to offer it to future generations, behind the bridges between periods it is also an awakening of consciousnesses through conservation that he is trying to stimulate, and the spread of information is, in this respect, the core of the process. The stage that follows this line of thinking (and the responsibility of the spectator as much as the politician), stems in particular from the essential issues represented by access to knowledge and education. At a time that was of crisis and reconstruction Hannah Arendt wrote: “The role which, from Antiquity to our present day, all political utopias have ascribed to education, clearly shows how natural it seems to want to found a new world with those who are new by birth and by nature”, 7 she emphasises the importance of providing younger generations an education which will offer the essential tools for building a better world. By creating a link between the cultures of yesterday and those of tomorrow, Malek Gnaoui identifies and provides them certain vital tools for stimulating and enlightening minds. Because memory and education are the quintessential tools for the construction of tomorrow, Gnaoui’s message might be that, in a period marked by doubts and identity crises, we are made stronger and richer by an open consciousness and a knowledge of the past, especially by embracing these plural identities. When a philosopher questions political consciousness through historical conscience, they do so in parallel with a vital line of thinking about the concept of action, and it is perhaps by considering that “Silent action is no longer action because there are no more actors”, by interpreting the past and remembering the disappeared, Malek Gnaoui empowers the invisible by providing a voice in which to transcribe the present.

1-Alain Resnais and Chris Marker, Les statues meurent aussi, 1953

2- Vénus pudique, C.923, Musée du Bardo. Found on the site of the Odeon of Carthage, dated, according to the museum notice, in the 1 st quarter of the 2nd century of the common era.

3- Sami Kamoun, “Le bidonville de Djebel Lahmar, séquelle de l'ère coloniale : évolution morphologique et avenir architectural et urbanistique», in Al-Sabîl : Revue d'Histoire, d'Archéologie et d'architecture maghrébines [Online], n°6, Year 2018. URL: http://www.al-sabil.tn/?p=5150

4- AYEB Habib, Marginality and marginalization in Tunisia; Saida Manoubia in Tunis and Zrig in Gabes. (Arabic and English). AIHR. Tunis, 2013, [Online] URL : https://habibayeb.wordpress.com/2013/10/07/saida-manoubiaun-quartier-populaire-de-tunis-entre-marginalite-et-stigmatisation/

5- Habib Ayeb, idem

6- Essaïda, 1996, made by the director Mohamed Zran, broached through the friendship of Amine, a painter, and Nidal, a delinquent teenager, the reality of the popular streets of Tunis.

7-Hannah Arendt, La crise de la culture, (English title Between Past and Future, 1961), Gallimard, coll. “Folio”, 2002 (republication), p. 227.

8- Hannah Arendt, La Condition de l'homme moderne, (English title: The Human Condition, 1961), Calmann-Lévy

Matthieu Lelièvre