To put Tunisia on the global art map: This has been Selma Feriani’s mission for the last 15 years. Working between London and Tunis, the young gallerist has come up with one project after another, always with this goal in mind. Her passion for art dates back to her childhood: She grew up surrounded by Modernist painters from the École de Tunis that her pioneering mother, Essia Hamdi, represented through her own gallery, Le Violon Bleu, in the heart of Sidi Bou Saïd. ‘My childhood home was filled with paintings. My mother changed the hang constantly, like a moving museum,’ Feriani recalls in a French peppered with anglicisms. ‘We chose the works for our bedrooms even as children, we spent our weekends in artists’ homes, and our holidays centered around European museums. For me, art was a clear-cut choice.’

However, Feriani first chose to study finance in her hometown of Tunis, after which she followed ‘her dream’ and headed to London. For five years, she worked for a wealth management company, but every weekend she went to exhibitions in London or Paris. With her first salaries, she started a small collection of ‘artists from the Middle East and North Africa.’

In the end, she couldn’t relinquish her first love: art. So, in 2009, she opened her first gallery in Mayfair, London, featuring ‘artists I was in touch with, and who were terribly lacking in visibility’ – notably Nidhal Chamekh and Yazid Oulab, whom she still represents today. ‘Curators, collectors, I didn't know anyone: I had to learn everything from scratch. But my background in finance served me well in the complicated day-to-day management of the gallery. I like to be very organized: that’s how I run my house, my family, and my gallery.’ The early years as a gallerist were ‘really difficult. But my passion for the job kept me going – as well as my desire to show my mother that I could do it!’ Steadily, she caught the attention of London collectors, who began to share her enthusiasm.

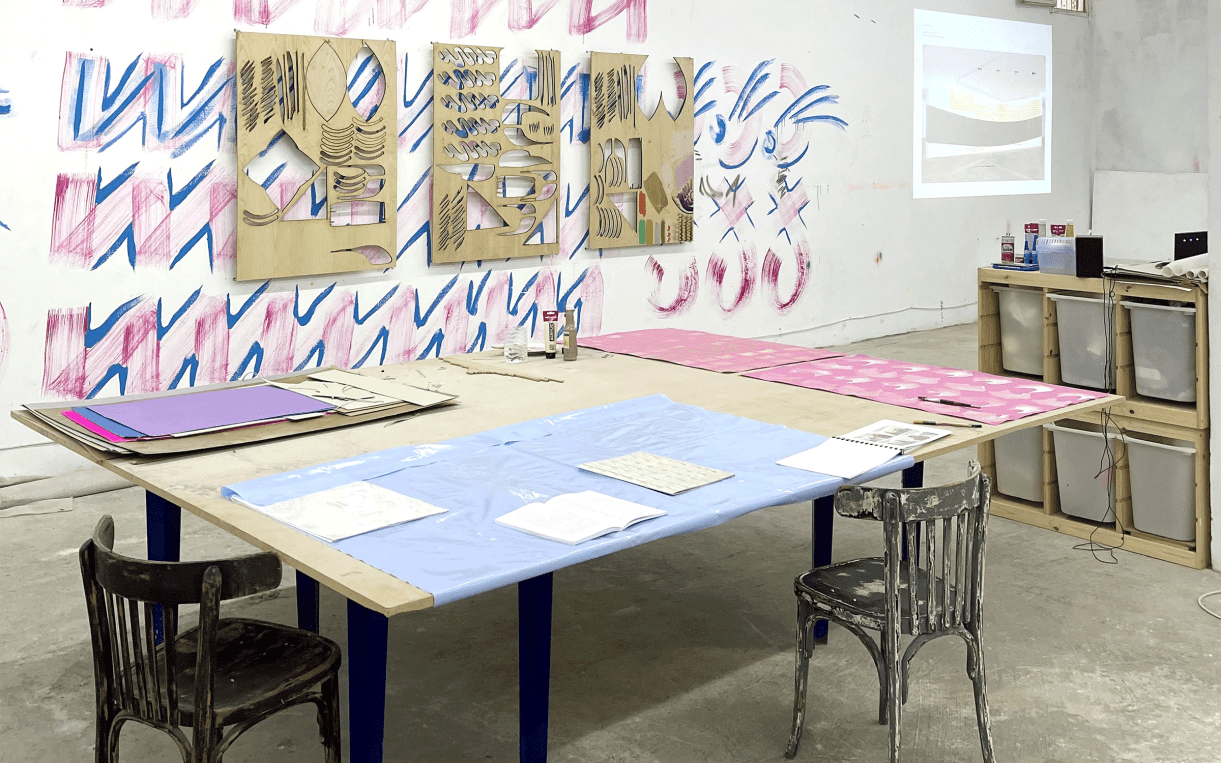

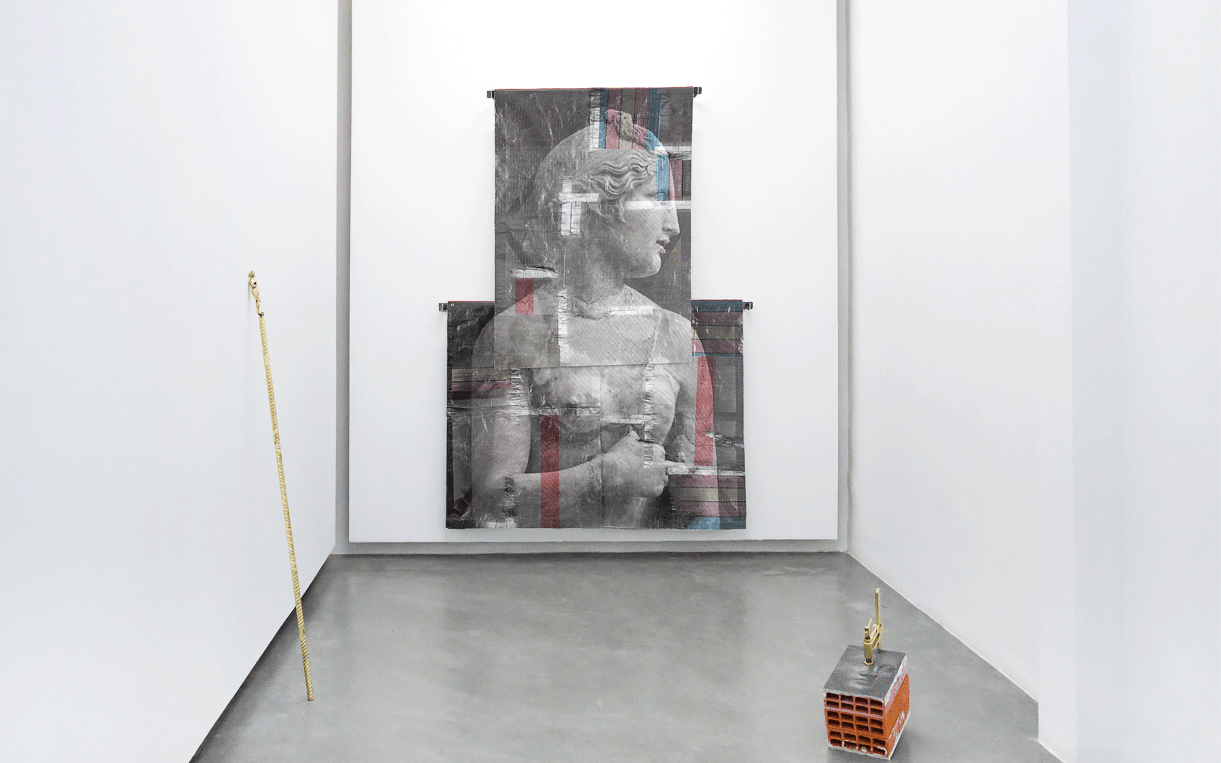

But she missed Tunisia. And the Arab Spring brought new hope. ‘Each time I returned home, I was frustrated by the lack of opportunities for artists, curators, writers. After the 2013 revolution, artists and all sorts of people reclaimed the public space and the city became a site of exploration. It was a revelation: I wanted to be part of this change.’ Feriani discovered an extraordinary space in the picturesque blue and white village of Sidi Bou Saïd, very close to her mother’s gallery. It was a former convent, which she purchased from the Vatican. ‘Rather than a white cube, I wanted to embrace the unique local architecture. The building has an incredible energy.’ A labyrinth of small rooms, it allows each artist to reinvent themselves. The space ‘forces you to push your limits, to get out of your comfort zone, to think of everything in situ.’ The lower production costs compared to London allow for ‘great flexibility: The artists really have carte blanche, and the gallery becomes purely experimental, without feeling any commercial pressure.’

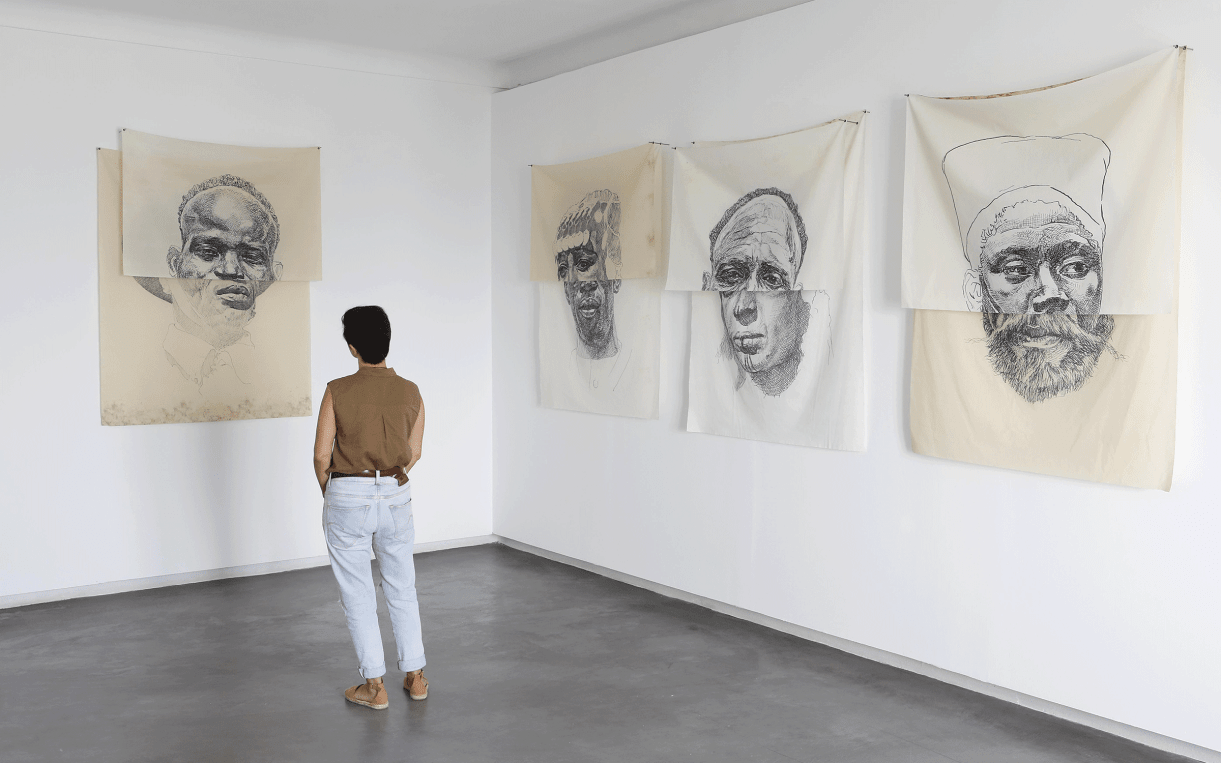

Passionate about artists who ‘question the environment, society,’ Feriani is rediscovering her region through their eyes. ‘This feeling of reclaiming your country is very powerful and moving. Tunisia is a wonderful resource, for foreign artists as much as for Tunisians: It has incredible light and 3,000 years of history, which offer infinite sources of inspiration.’ It’s clear that the gallery’s ‘DNA is Tunisian,’ and the program gives pride of place to local artists such as Jellel Gasteli and Nicène Kossentini. But, Feriani insists, ‘I also want to engage with artists from elsewhere, whether from Lebanon or Latin America. Nurturing the richness of different cultures meeting, that opening up: that’s what I thrive on, and that’s where new aesthetics emerge. The gallery has become an incubator for contemporary and multidisciplinary practices to develop and its gradually established its reputation.’

Tunisia is, admittedly, not known as a place with many collectors, and its artistic ecosystem is yet to flourish. So, how to make that happen? ‘By fostering new encounters at the gallery, we have pushed along a whole generation of new collectors, hoteliers, doctors, young entrepreneurs,’ Feriani says proudly. ‘We are also bringing in our friends from London. Another challenge!’ To entice them to Sidi Bou Saïd, Feriani organizes special weekends with openings, studio visits, elegant dinners, and excursions to the Bardo Museum in Tunis or to Carthage. And it works! ‘You know, life here is very pleasant. Even if the political mood is somber, we cannot be denied the beauty of our country!’

During the pandemic, Feriani was 100% invested in her projects. ‘I worked twice as hard to set up a residency in a disadvantaged neighborhood of Tunis. Sidi Bou Saïd is a very bourgeois village, which is fascinating from a historical and architectural point of view, but that isn’t the whole of Tunisia.’ And so, she chose a district where African communities from the Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Mali reside. She will select guest artists, whether or not they are represented by the gallery, based on ‘their interest in community engagement, in the Tunisian context.’

Despite her travel-heavy lifestyle, Feriani has already embarked on another project: constructing an 800 m2 space north of the capital, between Carthage and the airport, with storage, offices, and a library where events will be held. ‘Our artists have grown, many are established now, and naturally they want to make work on a larger scale. Hence the new location, scheduled to open in December 2023. It will be a very important space in Africa,’ she promises.

However, it is in London – where she hosts exhibitions at Cromwell Place four times a year – that she thrives financially. ‘Fairs are fundamental, of course. We have a natural link with London and France, but we have also had great success at Art Basel Hong Kong.’ The American market remains harder to break: ‘One of my goals is to develop a link with the United States, once we are more established. But I don't want to turn my back on Africa either, because our strength comes from belonging to this continent, which is right across Europe.’ After having invited First Floor Gallery Harare, from Zimbabwe, to collaborate in Tunis, the next step will be to participate for the first time in an African art fair in Cape Town next February.

Another priority, at the moment, is to strengthen ties with France: the gallery’s ‘second home and strongest market.’ Like London, Paris is an ‘open-air museum’ where Feriani learned everything she knows. ‘After studies at the Institut Supérieur des Beaux-Arts de Tunis, artists gravitate towards France to do their master’s degrees, and many settle there.’ To support these artists, Feriani maintains an ongoing dialogue with key institutions throughout France. ‘If they want to know about North Africa, they come to us. It’s still not plain sailing, but we are known and respected.’