Imen Zarrouk : Et si Carthage… ? (And what if Carthage…?) is the inaugural exhibition at Selma Feriani’s new 2000 m2 gallery in La Goulette. How did you approach it?

Nidhal Chamekh: The Et Si Carthage… ? project took shape two years ago, when the gallery was still an embryonic concept in the gallerist’s mind.

The creative process unfolded through the production of works and through discussions. A conversation with my colleague and friend Atef. M., who had already visited the gallery, raised questions about the imposing height that gives it an almost religious aura. This led to a crucial choice between directly confronting the work with the whole space and a more pragmatic approach, which we finally adopted: more down-to-earth, evoking ruins.

For the exhibition the gallery’s levels are conceived as “reading plans,” with the first space at the entrance for works and productions, the upper space a place for exploring ideas, influences, references, and other elements accompanying the project, such as research and music, and the basement, dedicated to video, an archival space containing what is buried and what lies beneath. Jean-Denis Bonan’s 2006 film [Carthage Édouard Glissant] is interpreted as an archive document.

Installation View of “Et Si Carthage…” at Selma Feriani Gallery. Courtesy the gallery and the artist.

IZ: What is Et si Carthage…? doing?

NC: It investigates recurring obsessions linked to my vision of the world. It seeks to offer an alternative reading of the past, challenging the linear conception of history taught in schools. It also questions how the present resonates with the past, creating constant reminders. My approach is inspired by Walter Benjamin, a Marxist and anti-linearist who explored how the past can haunt the present in ghostly ways and influence our reality.

Nidhal Chamekh, Crouching Venus with tabla, 2024. Plaster, tabla, wooden mask and steel. 270h x 90w x 100d. Courtesy the artist and Selma Feriani.

IZ: According to Gilles Deleuze, in art “it’s not a matter of reproducing or inventing forms, but of capturing forces.” Do you think about this in your practice?

NC: Yes, I’m familiar with this quote from Deleuze, who explores the capture of forces and vanishing lines. Benjamin touches on similar ideas, notably with his “dialectical images,” a somewhat obscure notion that appeals to me, leaving room for various interpretations. Theodor Adorno, in Minima Moralia, also evokes these Benjaminian ideas.

I’m more interested in conflictuality than resolution. Et si Carthage…? explores the tension between themes such as antiquity, the colonial question, and the contemporary challenges of migration. It seeks to find the thread of tension between them: proposing that Hannibal can speak to today’s exiles, and that today’s exiles can converse with yesterday’s colonized.

In my artistic approach, I instinctively move into unexplored territory. One example is my initial reflection on African influences on Roman art and culture during Roman colonization of North Africa. This naive questioning highlighted the lack of attention paid by historians at the time to the need to undertake a process of decolonization in archaeology.

Nidhal Chamekh dans l’Atelier. Photo by Hamza Bennour.

IZ: How do you reconcile your artistic commitment and your criticism of capitalism in the art world with being represented by a international gallery? How do you deal with criticism and maintain your artistic integrity?

NC: Fear of gentrification drives me to redouble my efforts to maintain a certain balance, by remaining involved in collectives and organizing despite the relentless production constraints imposed by the art world. I maintain maximum distance from the ruling class, favoring links with technicians and the manual side of my practice. Inspired by artists such as Francis Alÿs and Jannis Kounellis, I forge my own models even if it means losing certain opportunities.

IZ: How would you best describe your situation as a Tunisian living in Paris? Do you consider yourself an exile, a migrant, or a citizen of what Glissant called the “Tout-monde”?

NC: A citizen of the “Tout-monde,” with reservations about the liberal connotations it often has now. The idea of exile appeals to me more, not in its administrative definition, but existentially and politically. The term “exiliance,” as proposed by Alexis Nouss, encompasses a diversity of people, including both documented and undocumented migrants, creating a vast community of exiles.

Also, exile is not limited to those who physically leave; those who remain can also experience it, as described by Jacques Rancière. Exile is organically anti-neoliberal, contradicting individualism, as it often requires a community based on mutual aid and sharing. Exile as an experience is intrinsically communal, refuting the individualism often associated with those who leave.

Nidhal Chamekh, Mercurio coloniale, 2024. Plaster, steel, pith and helmet. 190h x 23w x 40d. Courtesy the artist and Selma Feriani.

IZ: Your investigation of African colonial history, which can be compared to that of an archaeologist, involves rewriting the historical narrative by giving voice to the “defeated.” How do you reconcile the seriousness of this approach with your playful, whimsical, and childlike side, where your imagination takes over?

NC: I don’t think I’m an archaeologist… I like digging, but it’s a bit like when I was a kid and I used to take a toy apart. It’s an inclination I’ve always had and there’s also a geeky side to it – I’m passionate about things that don’t necessarily show up in my work. If a new piece of software is useful, I might spend a month researching it.

Among those you call the defeated and whom I like to call the “losers,” there’s a form of intelligence that touches me deeply, a practice of bricolage, using with what there is. It is common among the less privileged of the Global South, including Tunisia.

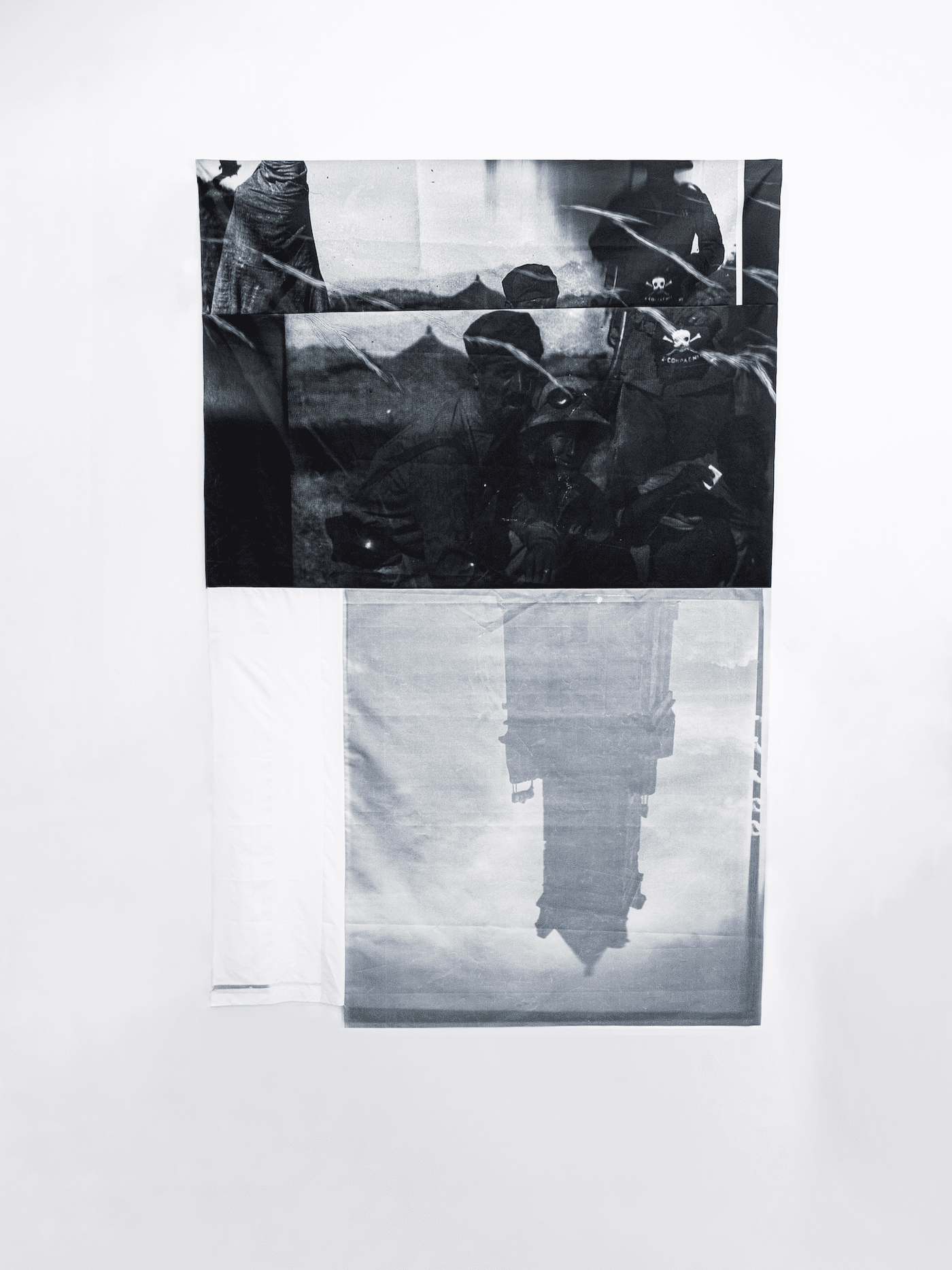

Nidhal Chamekh, Untitled, 2024. Transfer on fabric. Courtesy the artist and Selma Feriani.

IZ: Time flies, and almost a decade has passed since you took part in the 56th Venice Biennale, “All The World’s Futures.” What have you retained from that experience?

NC: Without the 11th Dakar Biennale of 2014, there would have been no Venice Biennale, either for me or for others of my generation. The Dakar Biennale was special, with three curators from very different geopolitical contexts. There was an unrivalled diversity of practices, approaches, and backgrounds.

The strength of that edition of the Venice Biennale went beyond its political aspect and strong African presence. It was the density of young talent, and the number of artists between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-five participating on that edition has not been exceeded. Okwui Enwezor took a lot of risks, involving different types of people.

Nidhal Chamekh, X,2023. Clay and fabric. Tribute to David Hammons. Produced in collaboration with Atef Maatallah – Nidhal Chamekh. Courtesy the artist.

IZ: Finally, what does Nidhal Chamekh dream of?

NC: In terms of my art practice, I aspire to a more comfortable situation with a larger studio. Despite the constraints of the art market, I prefer to take my time and produce slowly. My ultimate desire is to create even more slowly, to disappear, to free myself from the constraints of visibility.

I also want to devote more time to being politically and culturally engaged, both in Tunisia and in France.

Et Si Carthage…? is on view through 24 March 2024 at Selma Feriani in Tunis.

Born in 1985 in Dahmani, Tunisia, Nidhal Chamekh studied at the School of Fine Arts in Tunis and the University of Sorbonne in Paris. He continues to live between the two cities. Chamekh’s work situates itself at the intersections of the biographic and the political, the lived and the historical, the event and the archive. Spanning drawing, installation, photography, and video, it dissects the constitution of our contemporary identity.

Imen Zarrouk is an independent writer and curator, she worked at the Kamel Lazaar Foundation and was part of the team that launched the B7L9 one of the first independent art spaces in Tunis, Tunisia.